How Bluetooth got its name, an interview with Jim Kardach

Today, Bluetooth is the primary driver of wireless connectivity between electronic devices. But like most new technologies, there were plenty of challenges throughout its development and commercialization.

We spoke to Jim Kardach, the founding chairman of the Bluetooth Special Interest Group (SIG), which created the technology, to understand why it succeeded where so many similar initiatives had failed. He also revealed how Bluetooth earned the namesake of a famous Danish King.

Hi Jim, can you tell us more about your background?

Jim: Back in 1986, I came out of California State University Fresno with a Bachelor’s in Electrical Engineering. I started at Intel right away, and worked there for over 20 years, developing mobile architectures. During that time, I focused on low power design, CPU architectures and other technologies that were fundamental to notebook computers. If you look at notebooks today, a lot of their features are based on technologies that I patented during my time at Intel.

By the time you started working on Bluetooth, you already had experience with standards. Can you share more about that?

Jim: Yes, I had previously worked on power management standards.

When I first started working on them, I was the architect of the first system on chip (SoC) for notebooks, the 386L. As we were designing it, we wanted to do power management, so that when you closed the lid the computer would go to sleep, or if the hard drive would idle you could power it off. But to do that, you needed control of the operating system to be able to properly design the interrupt routines.

Back then, if you bought a computer, there were a lot of different operating systems – Xenix, DOS, Windows, etc. There were also different drivers for nearly every operating system, and just DOS alone had a huge variety, whether it was 8-bit DOS, 16-bit DOS, 16-bit 386-protected mode, and so on. The variety made it nearly impossible to implement this.

As a solution, we created a system management mode. It’s basically what virtualization is today. By creating a software layer below the operating system, the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) could then write their own management code. This allowed us to implement power management, regardless of what operating system was installed. It would generate an interrupt, go into system management mode, execute the power management routine, and then come back up to the OS/application.

This, however, left artifacts. For example, after resuming from sleeping, no time would pass because we would shut the CPU down (and the OS relied on the OS to keep time). So we created a power management standard (Advanced Power Management) which provided an interface between the OS and hardware to remove these artifacts (“hey OS, the system just resumed, you should fix your time”).

After this power management standard, we then did a cooperative power management standard called Advanced Power and Configuration Interface (ACPI) where we formed a royalty-free SIG. In 1996, we finally finished the spec in collaboration with other companies.

How did your involvement with these standards result in you leading the Bluetooth group?

Jim: The following year – in 1997 – my boss at Intel saw the need to integrate wireless technology into notebooks so that people could connect to the Internet. Although there was an IEEE group working on it – the 802.11 – they had not seen much success.

We couldn’t integrate cell phone connectivity, because nearly every country back then used different standards for it. Some used GSM, while others used TDMA only, and so on. Supporting so many standards was just too complicated and expensive.

At first, we started thinking about connecting a cell phone with a cable to a computer. Then the concept evolved into developing a low-cost radio. Around the same time, Nokia and Ericsson were working on similar concepts. We figured we should all get together and build one protocol that works across all devices. This would be far more valuable for the industry and for each individual company.

With all my work on standards, it was decided I would run the new Special Interest Group (SIG) which would eventually become known as Bluetooth, and serve as Chairman of the Board.

Who were the founding members of the Bluetooth SIG, and what did you set out to achieve?

Jim: We got the top two cell phone companies (Nokia and Ericsson), and the top two notebook companies (IBM and Toshiba) involved. We wanted to get Microsoft involved too, but ultimately couldn’t. With Intel leading the charge, that made five companies.

Our goal was to develop a wireless standard for connecting mobile phones and notebooks to other devices using short range, low-power, inexpensive wireless radios.

Bluetooth is so pervasive today. Was it always an obvious technology?

Jim: Not at all. In the computer industry, the networking people didn’t like it. They didn’t understand why you couldn’t just have the same usage model over a wireless local area network (LAN). But Bluetooth is actually the opposite use case.

“Many people didn’t understand the concept of a personal network, or even the concept of removing the wire between a mouse and notebook.”

With LAN, you have a bunch of people connected to the Internet on a public network. With Bluetooth, you have all your personal devices connected – phone, notebook, headset, etc. – to your own personal network. For this reason, we were actually considering the name personal area network (PAN) instead of Bluetooth initially.

Many people didn’t understand the concept of a personal network, or even the concept of removing the wire between a mouse and notebook. It was definitely a challenge.

How long did it take to get the technology off the ground?

Jim: Within about a year, we had introduced the 1.0 spec. One benefit we had going into it was that Ericsson already had a base radio to start with, and we modified it to add more features.

However, we quickly discovered that the radios weren’t communicating very well, so we published 1.0A shortly thereafter. After that, we decided we’d better publish the technology as version 0.9 – and wait until we got 3 bits of hardware interoperating to promote it to 1.0. It took another year to get to that point.

A lot of our challenges were around how to achieve high network density. Meaning, in a room I want 10 Bluetooth networks that don’t interfere with each other and have a high throughput. 802.11 broke down quickly because of interference – it didn’t work well for network or device density. We were optimizing for 90% throughput with 10 colocated networks.

Considering these difficulties, did you ever have any doubts that Bluetooth would catch on?

Jim: We definitely went through a lot of slumps.

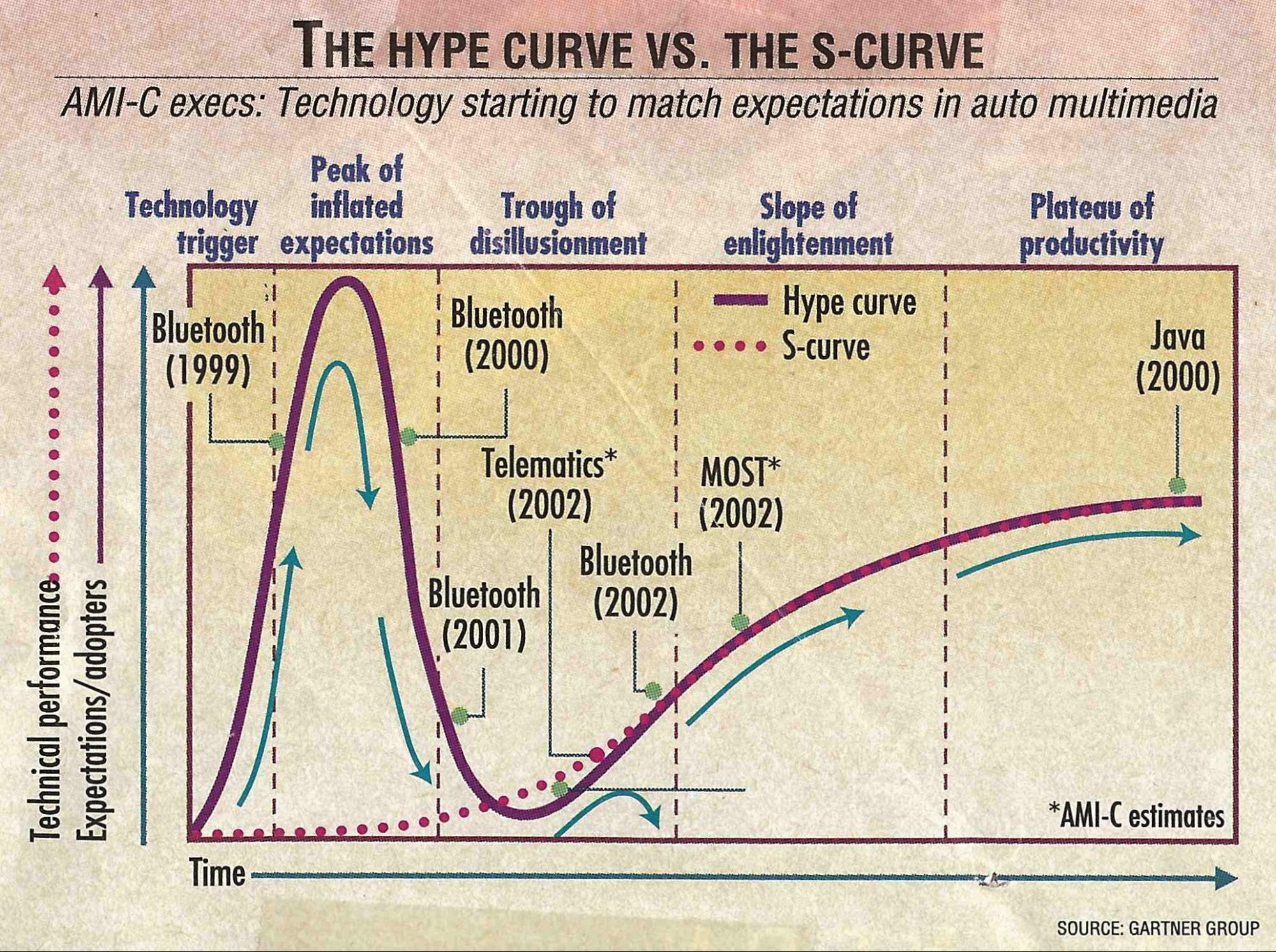

There’s a famous concept called “the hype curve”. A project starts off with a lot of fanfare, then goes down to the valley of disillusionment, and slowly comes back up. Someone on the team printed this out and put Bluetooth along it.

It’s important to remember that Bluetooth was developed during the Internet bubble burst, and the initial spectrum auctions, when the US government first started talking about cellular frequencies and auctioning them off, instead of giving them away. Companies like AT&T started realizing that if they didn’t win those auctions, it would ruin them, so there were unbelievable financial bids.

“The thing that helped us keep going was that no one in our group doubted the technology.”

This meant that all operators suddenly had no money, because they had spent it all to acquire their spectrum. This wasn’t just relegated to the US, either. Countries like France, Germany and others followed suit. All the telecom companies selling cell phones had money problems because of the spectrum auctions, and couldn’t take risks. This caused delays with the integration of Bluetooth.

On the PC side, the burst of the Internet bubble caused sales to slow. Integrating Bluetooth into a notebook was tough, because the market crashed and there was no money to do it.

The thing that helped us keep going was that no one in our group doubted the technology. We were dealing with managers who were doubting it, though, which made it challenging. But we believed in the technology, and so we just kept going.

Despite the early challenges, Bluetooth was ultimately a massive success. What do you think were the factors in its success?

Jim: I think a big factor of its success was how the IP licensing worked, and how that affected the interactions of the group.

When we decided to form the group, there were 2 different approaches we could have taken. We could have gone through a standardization body (such as IEC), or formed our own SIG to create a de facto standard (which is what we ultimately did).

Typically, the computer industry prefers to avoid standardization bodies, because they take too long. So we went the route of the de facto standard, and then later went to IEEE to get it formally recognized as 802.15.1.

Because of this, we also adopted an open IP model, which is something that greatly benefited us. It meant that every company involved would get a license to Bluetooth free of charge, and no single company made money from the adoption of that technology.

“Technology was presented based on its merit – not based on financial gain.”

This is in contrast to the way the telecommunications industry usually did licensing contracts, where the technology was licensed, and as a result, there was a huge financial gain for getting proposed technology adopted.

As a result of choosing an open IP model, technology for inclusion in the spec was presented based on its merit– not based on financial gain. Everyone argued about the best technology to use to further the goal, not to serve the interest of a particular company.

A lot of other technology specs died because there were fights about the technology which was based on patents that were owned by sponsoring companies. They could never get agreement and the efforts would eventually fragment and the technologies would then be introduced as proprietary specifications. Our goal was to allow everyone to use it free of charge because we wanted our products to be enhanced by Bluetooth (not to make money off Bluetooth).There were fights about the technology which was based on patents that were owned by sponsoring companies.

We were all in it for the technology — not for the financial again.

Why did the companies agree to invest in a technology they couldn’t directly monetize?

Jim: We reminded the companies that our job wasn’t to make money off Bluetooth directly. Instead, we were doing Bluetooth to make our products better.

As an example, I was once on a business trip and walked off the airplane and there was a huge sign – 10×5 feet – for Jaguar. It talked about 3 things: the V12 engine with horsepower, leather upholstery, and Bluetooth. Jaguar could have mentioned anything, yet there they were, bragging about a $1 radio in their car. We knew that all our companies would indirectly benefit from Bluetooth, because it would help grow the adoption of our technologies.

Where did the name Bluetooth come from?

Jim: I was at a meeting in Toronto, Canada, where I went to present the different usage models around another technology we were working on at the time, called HomeRF, with a consortium of companies, including Intel and Ericsson.

Sven Mathesson from Ericsson, a professor and the father of the CMOS Radio, was also there, presenting the specs of the radio.

We both presented and it didn’t go well. The Intel people who previously said they’d support us in the meeting didn’t, and the same thing happened with the people at Ericsson. It was my first taste of politics.

Sven and I decided to a do pub crawl on that cold fall evening, to debrief.

Since I’m a history buff, we started talking about history. Sven isn’t a huge history guy, but had happened to have just read The Long Ships, a book about the Vikings, and the King was named Harald Bluetooth.

When I got home, a book I had ordered from the folio society, “The Vikings” had arrived. Because I was working with all of these Scandinavian companies, I had ordered this book to understand their history. When I opened it, there was a big runic stone, the baptism stone of Denmark, with the second King of Denmark, Sir Harold Bluetooth, standing on top with his hand held up carved into the stone.

It was at that moment that I got a stroke of inspiration. I thought, ‘we really need a single name for our effort, I think Bluetooth would make a good name. It would be hilarious.’ I scanned it in, took out my sharpie and outlined Harald.

Up until that point, we had been referring to the technology by internal company names; Ericsson called it MC-Link, Intel called it Biz-RF and Nokia referred to it as Low Power RF. It was clear from Toronto that we really needed a single name (I presented about Biz-RF, and Sven presented MCLINK).We had been referring to the technology by internal company names; Ericsson called it MC-Link, Intel.

On Monday I went to Simon Ellis, the marketing guy and said, “I think we need a single code name, How about Bluetooth?”

Simon thought it was a terrible name, but I showed him the picture, which he thought was great. He asked if I could add a notebook and cellphone in Harald’s hands. I took out my sharpie and made some changes.

We laughed about how funny it would be to hear Bill Gates or Andy Groove having to say the word Bluetooth.

“Management will never approve this,” he added.

We decided that I would lay the Bluetooth slide on our VP’s (Stephen Nachtsheim’s) chair and if he didn’t say anything it would be approved. Like most VPs, he was traveling…

At Intel, anytime we used a codename, it was required to do a trademark search (Intel had a problem with people suing us because we used a word that had been trademarked). Intel required us to use names of mountains or rivers (since they’re hard to trademark) as codenames, but I decided to send Bluetooth to our lawyer anyway. He responded “Nice try, Jim. Give me a river or town in North America.”

I didn’t hear from him for two weeks, but then he actually wrote back. “Surprise, no one has trademarked Bluetooth.”

Shortly thereafter, we traveled to Lund, Sweden, to officially form the SIG. Ericsson and Nokia were competitors, just as Toshiba and IBM were; which left Intel as kind of a neutral company, like Switzerland, to be the leadership of the Special Interest Group (SIG). I was appointed chair of the SIG and Simon in charge of marketing.

During a meeting when everyone was talking, I said, “OK, we have an issue, we’re going to build this low power radio, but we haven’t decided on a code name. Some are calling it MCLINK, some BIZRF. We’re going to use the code name Bluetooth.”

All of a sudden, there was dead silence. Everyone stopped talking. And then Simon said that marketing was going to choose a real name. Everybody started to immediately discuss prospects for the name. Ericsson was thinking “Flirt” would be a great name, getting close but not touching, while Nokia liked Conductor (the hopping pattern of the radio could be compared to a Conductor getting all of the orchestra instruments playing together).

Next thing you know it was February, and marketing still hadn’t chosen a name. Back then, Bluetooth didn’t roll off your tongue the way it does now. So Simon offered a $500 reward for a name submission that would end up being the official name of the SIG and technology.

IBM had PAN, for Personal Area Network, which we thought could work. We met again in May, and finally, all voted and agreed on PAN. A couple of weeks later, I got an emergency call from Ericsson’s lawyer – PAN was really bad, because in an internet search, there were 1 million hits, so it was not trademark-able. We needed to find a non-trademarked name in time for the launch.

But guess which name we had done a trademark search on? That’s right, Bluetooth! From then on, everything changed to Bluetooth.

During the launch, we still had many disagreements on the name. We had hired the big PR firm Edelman, and even they didn’t want to use “Bluetooth”. We had also made granite runic stones, like in the picture of Sir Harold Bluetooth, and they did not want to hand these out to the press, as they thought they were too embarrassing. Simon looked at them and said “Who’s paying who? I’m paying you. You will talk about Bluetooth”, to which they answered, “We’re not gonna give out that stupid rock.”

Ultimately, the launch was hugely successful. The press loved the name Bluetooth, named after a 10th century Viking King. Once you’ve heard Bluetooth, it’s kind of hard to forget.

In the end, Edelman won an award for the best launch for Bluetooth that year. We forced them to do a thing they didn’t want to do and they became famous for it.

It’s funny that the name took off so well. Intel spent millions coming up with Pentium and associating it with CPUs. We spent zero dollars with Bluetooth, and the press loved it. Everyone started their articles with the story of how Bluetooth was named after a 10th century Viking King.

Of course, I reminded Simon of the $500 reward for choosing the name. He only paid me $200.

What advice do you have for engineers bringing new technologies to the market?

First, set clear goals that will make a big impact. For us, it was to get rid of cables.

Second, if you’re working with standards, know that formal standards are very difficult to do quickly. Typically, companies don’t want to wait that long, so you might want to consider de facto standards. In that case, make sure you understand the difference between royalty and open IP licensing. It’ll drastically affect the interaction.

Finally, do marketing.

Where are the groups’ members today?

We’re all friends. We talk every day.

We had conflicts during the creation of Bluetooth, but they were the good, healthy types of conflicts about how we can best achieve our goals. We trusted each other.

Wondering what the top Bluetooth technologies are in the market today? Check out our blog on the top 10 Bluetooth modules and components.

Comments (4)

Arjan van Dijk

March 12, 2019 at 7:33 pm

No word about the inventor of Bluetooth, Jaap Haartsen?

Andrew

March 22, 2019 at 12:37 am

What a great story.

Thank you for sharing it.

In particular the hype curve

Andrew

ANDREY PRONIN

March 28, 2019 at 7:54 am

Thank you for the article. It is very interesting.

Fausto Bini

March 29, 2019 at 4:19 pm

I like the creative intuition of the name; it wouldn’t be a maverick like it is if it had another “normal” name.